Implantable subacromial balloon spacers - New update from the Lancet

Article review of Metcalfe et al., (2022)

Paper title and link to paper:

Subacromial balloon spacer for irreparable rotator cuff tears of the shoulder (START:REACTS): a group-sequential, double-blind, multicentre randomised controlled trial (Metcalfe et al., 2022)

Overview of the paper:

Chapter three of “The Shoulder: Theory and Practice” by Lewis and Fernández-de-las-Peñas (2022) focuses on the burden of shoulder pain and disability. In this chapter, they discuss how a minority (~12-15%) of patients presenting to primary care with shoulder pain incur a large majority (~70-75%) of the economical burden associated with shoulder pain (Kuijpers et al., 2006). These high costs are largely down to sick leave from paid work but also include medical expenses such as physiotherapy, corticosteroids, and surgery.

When new technology or procedures are developed, it is important we take graded steps to ensure that any changes to current practice is the right one in improving clinical practice. The Lancet published a paper last week on the InSpace Balloon made by Stryker. This is a biodegradable balloon filled with saline that is surgically inserted between the humerus and acromion. The aim of the surgery is, as quoted in Stryker’s website:

“To reduce friction between the acromion and the humeral head or rotator cuff to allow smooth gliding of the humeral head against the acromion” (Stryker, 2020)

So essentially the technology aims to minimise “impingement”. I won’t go into detail on the impingement model in the shoulder as I have talked about this in a previous blog, but if you want to learn more I would highly recommend this interview with Jared Powell on the topic.

A recent systematic review (Johns et al., 2020) suggested implantable subacromial balloon spacers are a cost effective surgery which show improvement in function and range of movement with minimal complications. The authors did however suggest that these findings needed to be taken with caution due to a low level of evidence coming from retrospective studies with a high risk of bias. This bias included studies where there was funding directly from the manufacturer and the involvement of researchers who were employees or own stocks in the manufacturing company.

Methods

This then leads us onto the paper we are talking about today by Metcalfe et al., (2022). This study was a group-sequential, double-blind, multicentre randomised controlled trial. If you are not familiar with a group-sequential design (like myself), it seems to be a design where the data from the primary outcome measure is monitored through interim analyses at prespecified points throughout the trial when certain rules or boundaries are met. The trial can then be stopped at these interim analyses if there is sufficient evidence of the presence or absence of an effect in the primary outcome measure (Kelly et al., 2005). A group-sequential design is useful when there is uncertainty of the treatment effect as this affects the sample size needed to adequately power the trial. This allows the trial to be completed in a timely manner and minimise wasting resources on a larger sample. If a treatment is seen to be effective it can be implemented quicker into clinical practice. Alternatively, if the treatment is ineffective, the trial can be stopped to minimise any unnecessary harm to patients (Bhatt et al., 2016; Meurer and Tolles, 2021). This type of design does however have some downsides which we will touch on later and how it relates to this study.

The authors compared biceps tenotomy only (debridement only group) to the biceps tenotomy with the added insertion of an InSpace Balloon (debridement with device group) in those with irreparable cuff tears. After surgery, both groups were offered the same rehabilitation including a home exercise programme and a minimum of three face to face physiotherapy sessions. The Oxford Shoulder Score (OSS) was the primary outcome measure. This outcome measure, along with other secondary outcome measures such as the EQ-5D-5L, active range of movement, and Patient Global Impression of Change (PGIC), were assessed at 3, 6 and 12 months.

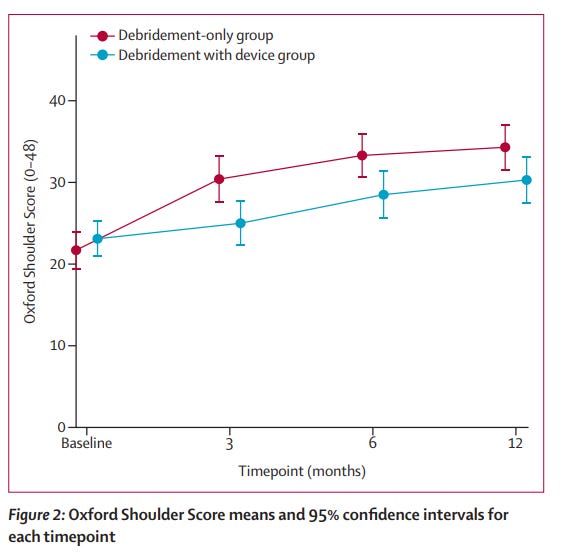

Just after two years of recruiting, the trial stopped after having recruited and randomised 117 patients. The results of the primary outcome measure is shown in the following figure:

In terms of the descriptive results of the primary outcome measure (the higher the better in this outcome measure), the mean difference was 4.2 in favour of the debridement only group. This was reported as a significant finding even when adjusting for baseline OSS scores, sex, tear size, and age group. As for the secondary outcome measures, there was a trend towards agreeing with the primary outcome measure but no significant difference was found.

Secondary outcome measures

There may be a few things to consider when we scrutinise the secondary outcome measures. Let us take the EQ-5D-5L scores (the higher the better in this outcome measure). At baseline, the debridement only and the debridement with device group scores were 0.501 and 0.486 respectively. This improved to 0.667 and 0.590 respectively. Although an improvement was seen, this did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.24). As we talked about earlier in this blog, there are some downsides to using a group-sequential design and this may be one of them. The decision rule to stop the trial is based on the primary outcome measure and not the secondary outcome measures. This means that the stopping point of the trial may be not as precisely estimated for the secondary outcome measures (Meurer and Tolles, 2021). For example, if the trial was run for longer with a larger sample size, would this reveal a significant difference or would this just continue to be non-significant?

Another aspect we need to be aware of when looking at the secondary outcome measures in this trial is that it was completed during the coronavirus pandemic. Here are some results I have pulled out of the pain free active abduction range of movement, a secondary outcome measure:

- Debridement only group

Baseline: 76.3° (n=58)

12 months: 124.1° (n=12)

- Debridement with device group

Baseline: 63.9° (n=51)

12 months: 87.1° (n=11)

Just looking at the range of movement differences from baseline to 12 months, you can see some marked improvements in the debridement only group. However, when you look at the number of patients (shown as n=) at the 12 month time point, you can see a huge drop off in the number of patients assessed for this outcome measure. This is because the measure was done in person and could not be performed to a large proportion of participants due to local coronarivus restrictions during the pandemic. Therefore we cannot be confident with these findings.

Conclusion

Before wrapping this all up, I want us to revisit back to where we first talked about the burden of shoulder pain. At 6 to 12 months after first presenting with shoulder pain, 40-50% of patients still experience persistent pain which impacts on their everyday life (Lewis and Fernández-de-las-Peñas, 2022). In the study we have discussed, at 12 months, both groups still had 49% of participants taking pain medication. Although the authors did not specify if this was directly for shoulder pain, this number is fairly high. Even if only half of these participants take pain medication for their shoulder pain, this still represents a large proportion of people with persistent shoulder pain. For me this highlights that we still have a way to go in reducing the burden of shoulder pain.

As for the conclusion for this study, I think I will leave you with the last sentence of the paper…

“The InSpace device is unlikely to be of benefit and might be harmful; therefore, we do not recommend use of the device in this population” (Metcalfe et al., 2022)

As always, if anyone has any comments, further reading or suggestions on this topic please feel free to fire them at me on here or on my Twitter. I am always learning and any discrepancies on what I have written is thoroughly encouraged.