Hydrodilatation as a treatment option for Frozen shoulder

Article review of Makki et al., (2020)

Paper title and link to paper:

Shoulder hydrodilatation for primary, post-traumatic and post-operative adhesive capsulitis (Makki et al., 2020)

Overview of the paper:

The optimal treatment for Frozen shoulder is not well understood. A recent large randomised controlled trial, The UK FROST trial, found no clinical superiority between steroid injection and physiotherapy, capsular release or manipulation under anaesthetic (see figure from the study below).

The authors did note the positives and negatives of the three interventions:

Steroid injection and physiotherapy could be accessed quickly (via the NHS) but more patients required further treatment

Manipulation under anaesthesia was the most cost-effective but had the longest wait times

Arthroscopic capsular release resulted in the least number of further treatments but carried higher risks and costs

One of the critiques from a correspondence in the Lancet by Mamarelis and Moris (2021) was that hydrodilatation was not included in the study. Hydrodilatation is a procedure (see video by shoulder surgeon Tony Kochhar) in which there is an arthrographic distension of the glenohumeral joint whereby the capsule is either stretched or ruptured. The authors (Rangan et al., 2021) of the UK FROST trial replied to this correspondence by highlighting how hydrodilatation was not common during the study period and that “Evidence to support its use remains scarce” pp.372. Rangan et. al., (2021) did however note how a Delphi process in the UK is underway to see if a trial in the UK is feasible.

This then leads on to the paper that I recently read in Shoulder and Elbow. Makki et al., (2020) carried out a retrospective study of 250 patients in the UK receiving hydrodilatation who had "failed physiotherapy”. These patients included those with primary (absence of intrinsic pathology) and secondary (post-trauma and post-op) frozen shoulder.

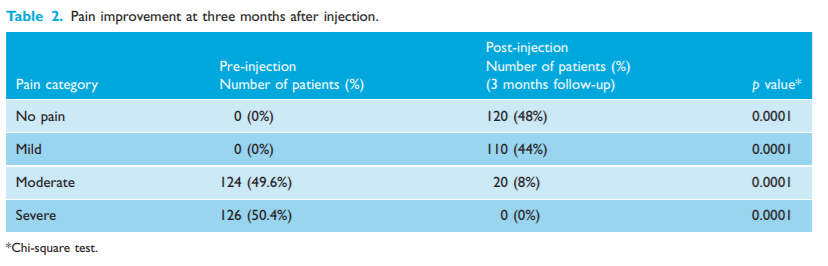

As you can see in the table below, the patients pain seemed to improve with nearly half of the participants reporting no pain at 3 months.

As well as pain, the patients range of movement, as shown in the table below, also seemed to improve.

The authors did report that 34 patients required further treatment. All but one of these patients were from the idiopathic group. Of all the diabetic patients in the study, 73% (or 20 out of 27 patients) needed further treatment. This was considerably higher than those without diabetes, with only 6.2% (or 14 out of 223 patients) needing further treatment.

The main critique of this paper, which could also be said of the UK FROST trial, is not including a control group. What happens if we leave these patients alone? Would natural history over a three and twelve month period show similar outcomes? I think it would be silly to dismiss this study and hydrodilatation as a treatment just because they did not have a control group but the question I want to know is how valuable is this intervention to the patient. When discussing treatment with a patient, I want to ensure I have a good understanding of the risks and rewards of different treatment options and then inform the patient of these options to allow the patient to make an informed decision.

Aside from this critique, I have taken two things from this study.

Hydrodilatation is a potential useful option for those patients struggling with pain and movement loss due to frozen shoulder. Further research is needed to look deeper into this treatment and comparing it to other interventions or a control treatment

Diabetic patients seem to get hit harder by the effects of a frozen shoulder as shown again in this study by how they are more resistant to treatment. This is consistent with further observations on this group (Dyer et al., 2021).

As always, if anyone has any comments, further reading or suggestions on this topic please feel free to fire them at me on here or on my Twitter. I am always learning and any discrepancies on what I have written is thoroughly encouraged.